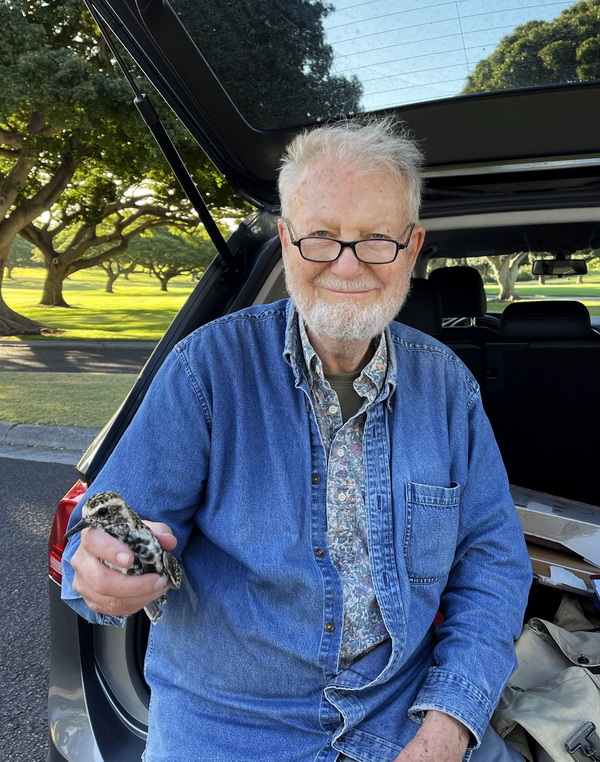

Dr. Wally Johnson with feathered friend, National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. ©Susan Scott

March 30, 2022

Our Kolea’s long-term advocate and life-long researcher, Dr. Wally Johnson of Montana State University, has been on Oahu these last few weeks helping the world learn more about one of Hawai’i’s (and Wally’s) favorite birds. In a study supported by Brigham Young University-Hawaii, the Hawaii Audubon Society, the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, and enthusiastic volunteers, Wally is placing leg bands on nearly half of the 60-to-70 Kolea that forage in the cemetery each winter.

Above: These ID bands are visible on foraging birds (binoculars or enlarging photos help.) To report a banded bird, note which bands are on which leg. This bird has blue on left leg, yellow and aluminum on right. ©Susan Scott

Each of 30 birds gets three leg bands, two plastic in various colors, and a numbered aluminum one, recorded by the North American Bird Banding Program. The colors allow observers to identify an individual without disturbing it.

This is how we know that Mr. X, a Punchbowl plover, is at least 19 years old. Wally gave the bird two red plastic leg bands (one went missing last year), and one aluminum, in section X in April, 2004. He says “at least 19” because the bird’s age was unknown when banded and, therefore, may be older.

Of the 30 plovers in Wally’s current study, 10 are fitted with tiny backpack tags that send GPS signals via satellite twice a day for about six months. Another 10 will carry identical tags sending no signal. The last 10 have only leg bands. This fall, Wally will be back to monitor the birds’ survival.

The plover carries its lightweight satellite tag on its back with soft, stretchable straps around the upper part of each leg. This allows the birds to walk and fly unhindered. ©Susan Scott

The 10 with signals will hopefully show the birds’ movements here in Hawaii, their tracks to Alaska, their nesting sites, and tracks back to Hawaii. The 10 with no signals will test the possibility that electronic tags interfere with natural navigation cues. Survival of the 10 with bands only will test whether simply carrying a backpack tag negatively affects the bird’s natural navigation system.

Volunteer, Marcy Katz, enjoys holding a satellite-tagged bird (antenna below its tail) before releasing it. Because Pacific Golden-Plovers defend their foraging areas, Wally makes sure each bird is returned to its home patch to avoid squabbles. ©Susan Scott

I’m smiling as I write the above paragraphs, because it sounds simple. It is not. Studies like this require years of experience. Nor do scientists just go to a store and buy satellite tags. At $1,600 each, these devices must be specially ordered and used in a timely manner, given limited shelf life of the batteries. Lastly, you have to catch birds that are crackerjack fliers and experts at avoiding capture.

Ornithologists catch birds for study by stringing up gentle traps called mist nets, similar to badminton nets except longer, and so fine they’re hard to see. But the wily Kolea can see them even in dawn’s early light. Mist nets, therefore, must be assembled in the dark. The team’s headlamp work begins at Punchbowl at 4:30 AM.

Nightwork by (from left) Dr. Wally Johnson, Sigrid Southworth, Diane Smith and Dr. Wendy Kuntz. ©Susan Scott

Wally Johnson is expert at freeing Kolea from mist nets. Kolea are docile once caught, neither kicking nor pecking, but seemingly accepting their fate. Volunteer Diane Smith reassures the bird that we mean well. ©Susan Scott

BYUH Biology Professor, Dr. David Bybee, drove with a student from Laie to Punchbowl several times to help with the study. Here David helps take down a mist net. ©Susan Scott

After dawn, comes the careful untangling of netted Kolea (1-to-4 each time), as well as mynahs and bulbuls that had the bad luck to fly into the nets. Packing up poles, nets and decoys, and then applying bands and devices to the plovers takes workers into daylight hours.

Unlike Kolea, mynah birds (left) and bulbuls struggle in the nets, getting their feet and wings more tangled than Kolea.

Those of us who have helped Wally agree that this is well worth getting up at 3:30 AM. The work of catching, banding, and placing satellite tags on Kolea is a grand life experience, especially with Wally who is kind, generous, and always the patient teacher. As for expertise, Wally is the man for the job. When a security guard asked how long he’s been doing this, Wally replied, “Five decades.”

Wally says that holding a plover always makes people smile. The photos of volunteers here prove his point:

Dr. Wendy Kuntz is a biology professor at KCC, and Hawaii Audubon board member.

Dr. Yvonne Chan teaches science at Iolani School and is also a board member of the Hawaii Audubon Society.

Retired Kamehameha Schools librarian and longtime friend of Wally, Sigrid Southworth, (left) showing her T-shirt to a banded Kolea, about to be released by Pat Moriyasu, Hawaii Audubon Board member.

Hawaii Audubon’s Executive Director, Dr. Susanne Spiessberger, experiencing the joy of releasing a tagged Kolea. ©Susan Scott

Liz Kumabe Maynard, leader of the Hanauma Bay Education Program, and also a Hawaii Audubon board member, has the pleasure of letting a plover fly off.

Because of Covid concerns, Wally is not giving a slide-show this spring. He’ll be back in October, though, to monitor the three study groups, and to remove the birds’ backpacks. The Hawaii Audubon Society will arrange one of Wally’s popular talks. Check out www.hiaudubon.org What We Do/Events for time and date, as well as for tours and other doings.

I know all plover lovers join me in thanking Wally for his continued efforts to help our Kolea thrive by learning more about them. Wally is science advisor for this Kolea Count, the first of its kind in Hawaii. All observations help us understand more about these marvelous native birds.

Our Big Count and Little Count ends March 31st, but data collecting is year-round. Kolea watchers, please record when your birds leave (or the last day you saw yours). Also, report birds that do not migrate (June only so as not to count later leavers or early returnees.)

In mid-to-late July, we’ll be celebrating Hawai’i’s first returnees, which marks the start of the 2022-2023 Kolea Count. Come October, we’ll also be celebrating the return of our special migratory researcher, Wally Johnson.

This Kolea rests in the loving hands of Laura Zoller, the Hawai’i Audubon Society’s Office and Communications Manager. ©Susan Scott

Read more about Kolea and other Hawaii Audubon Society projects at https://www.susanscott.net/kolea-white-terns-and-wedgies/

Subscribe to my blog at: https://www.susanscott.net/#subscribe-container