I count. Sign me up

November 12, 2023

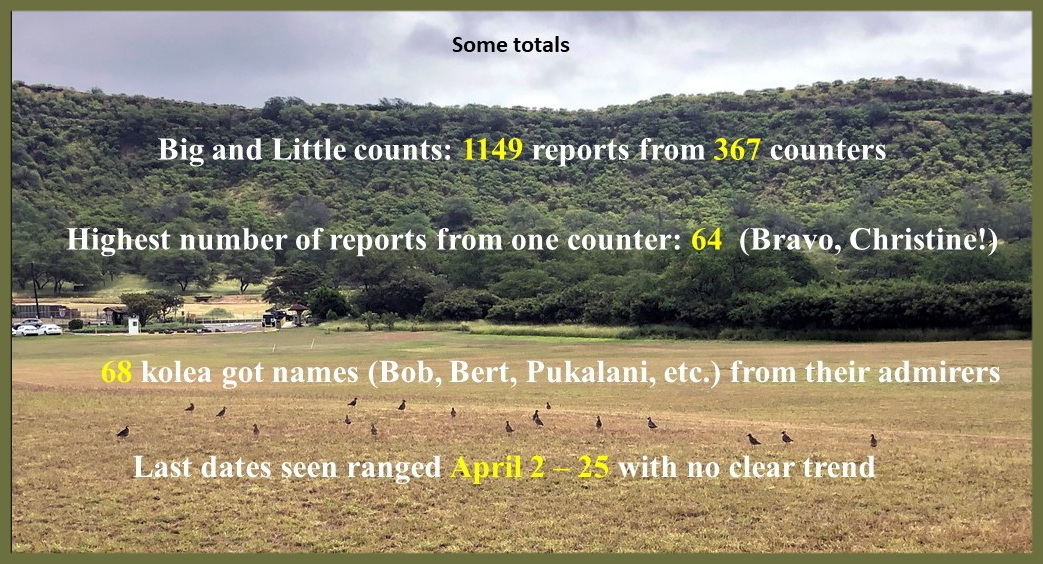

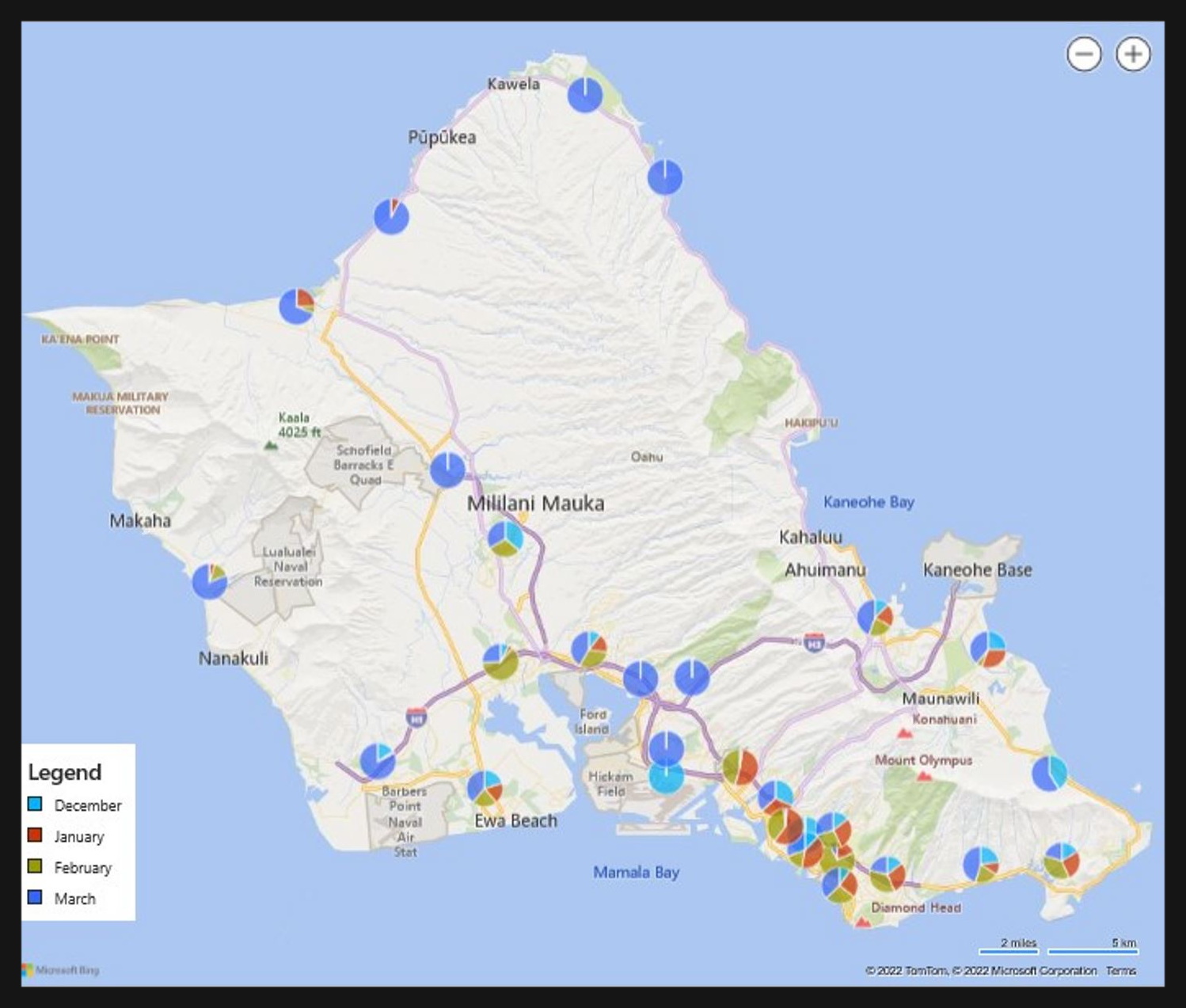

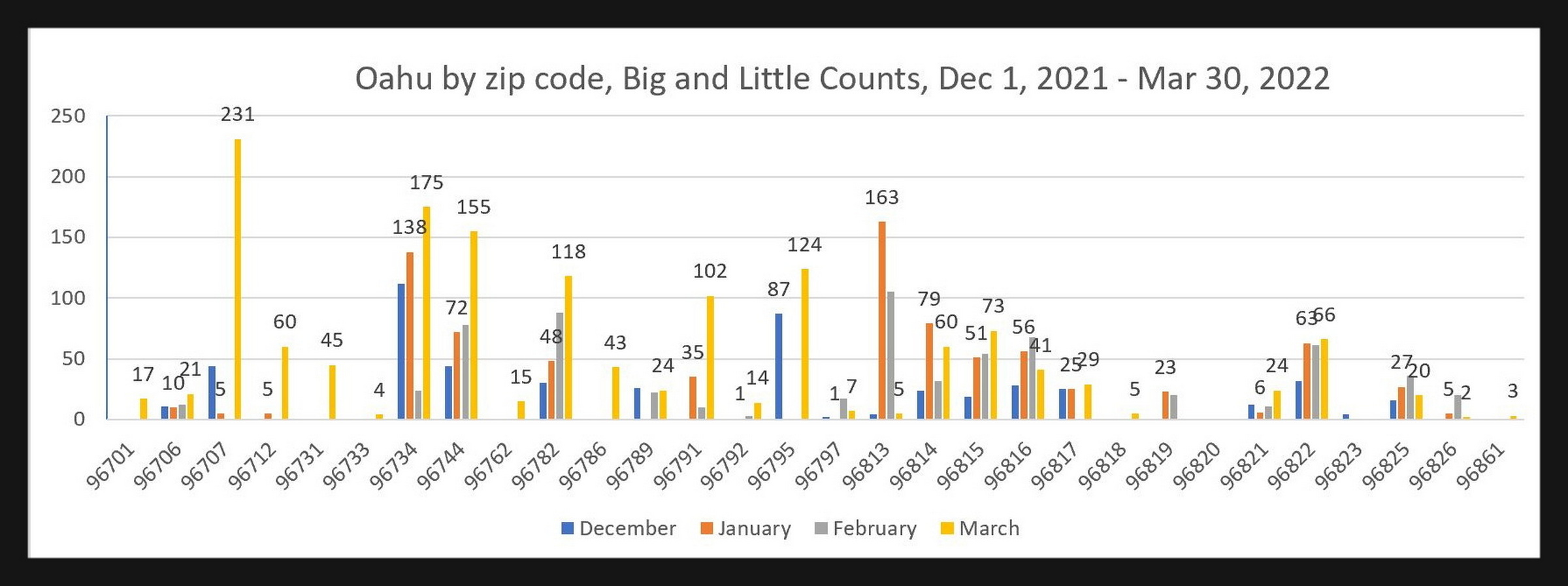

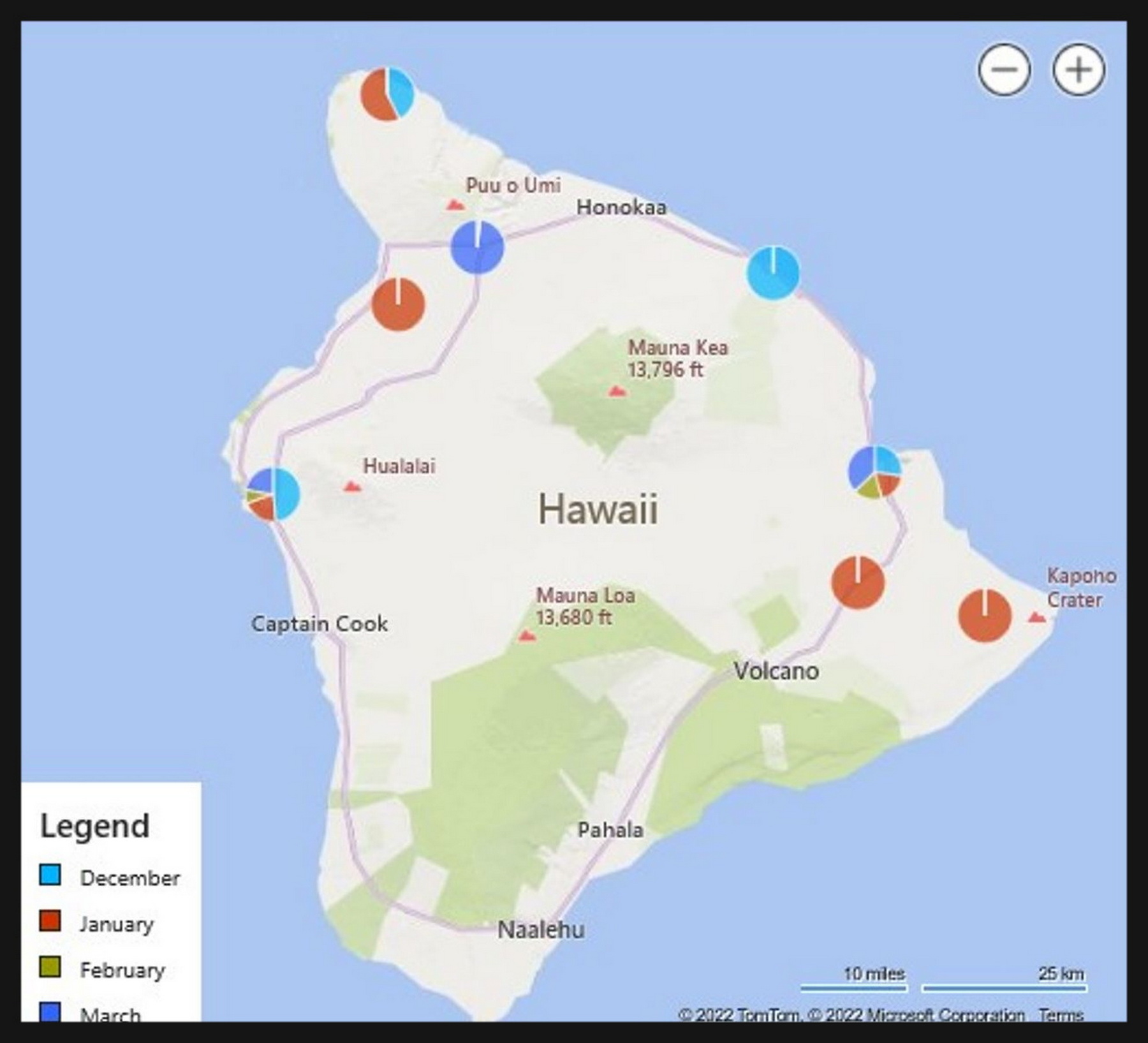

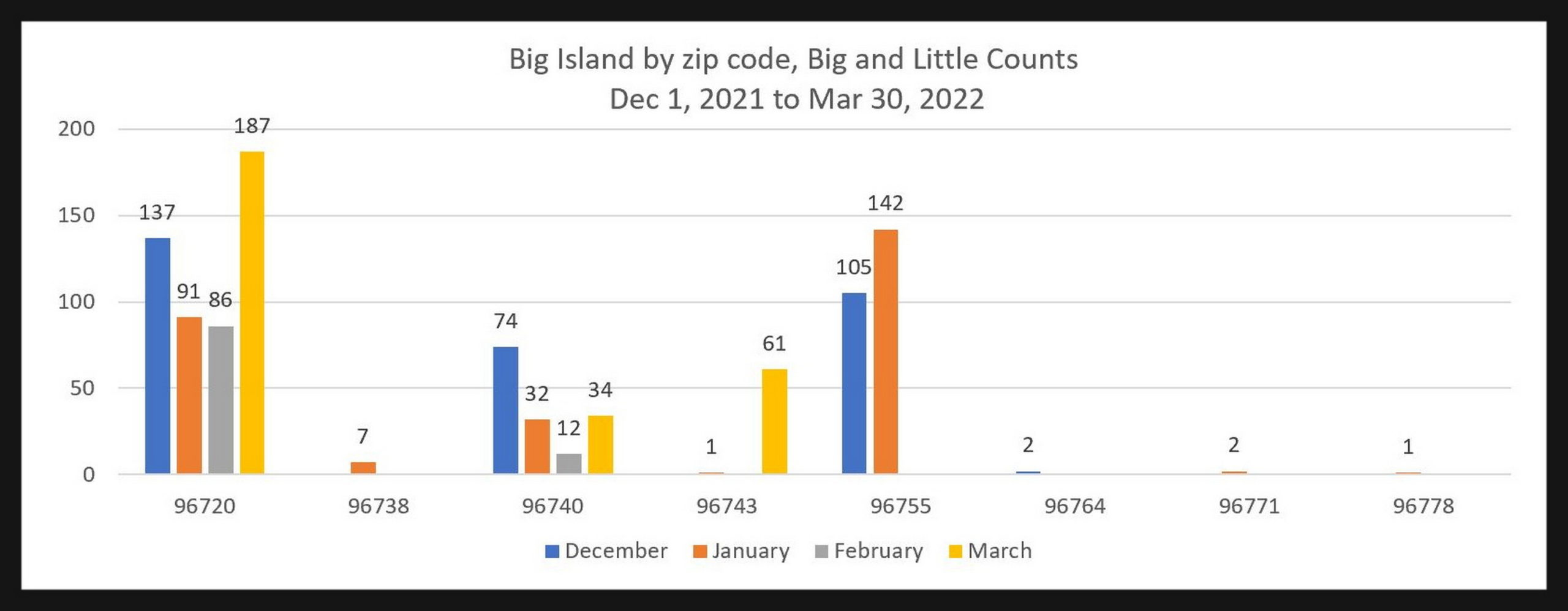

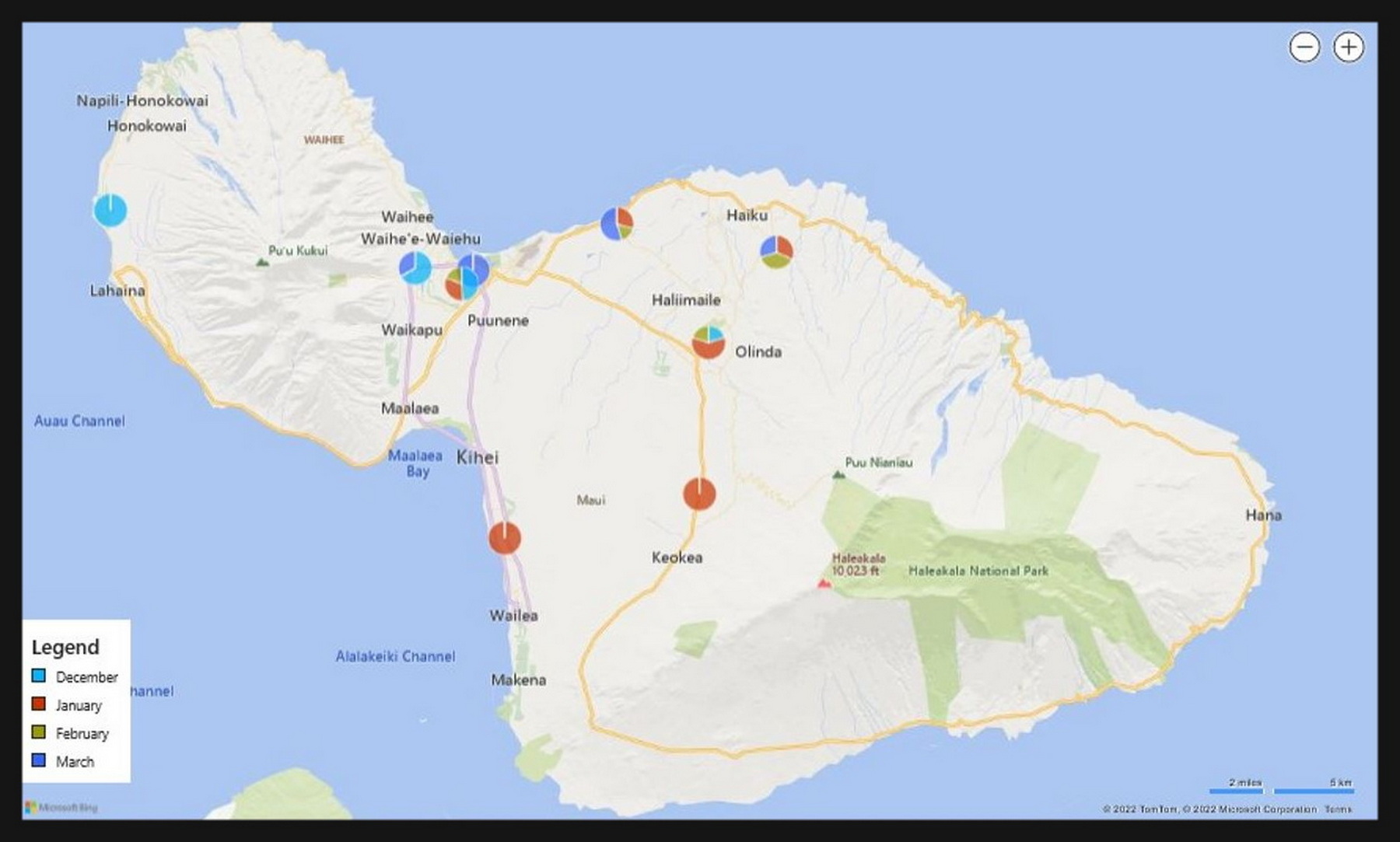

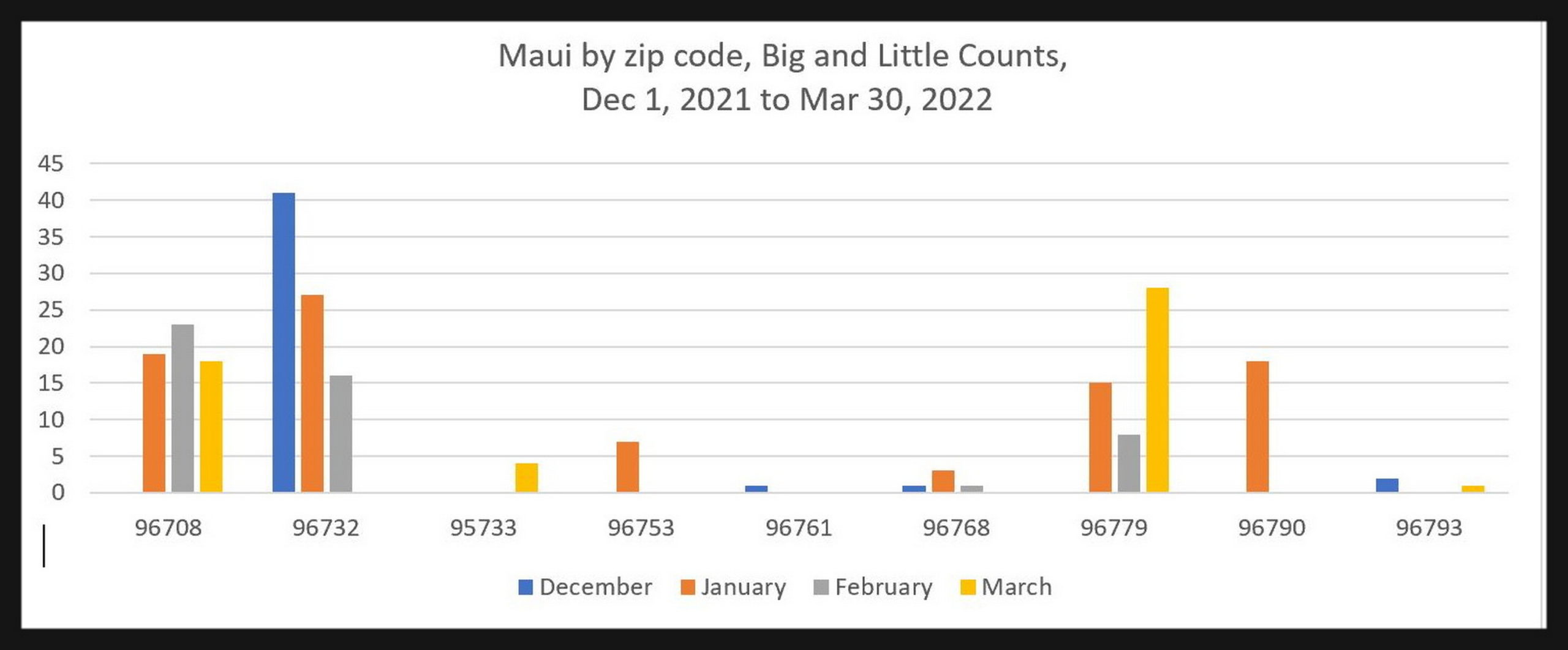

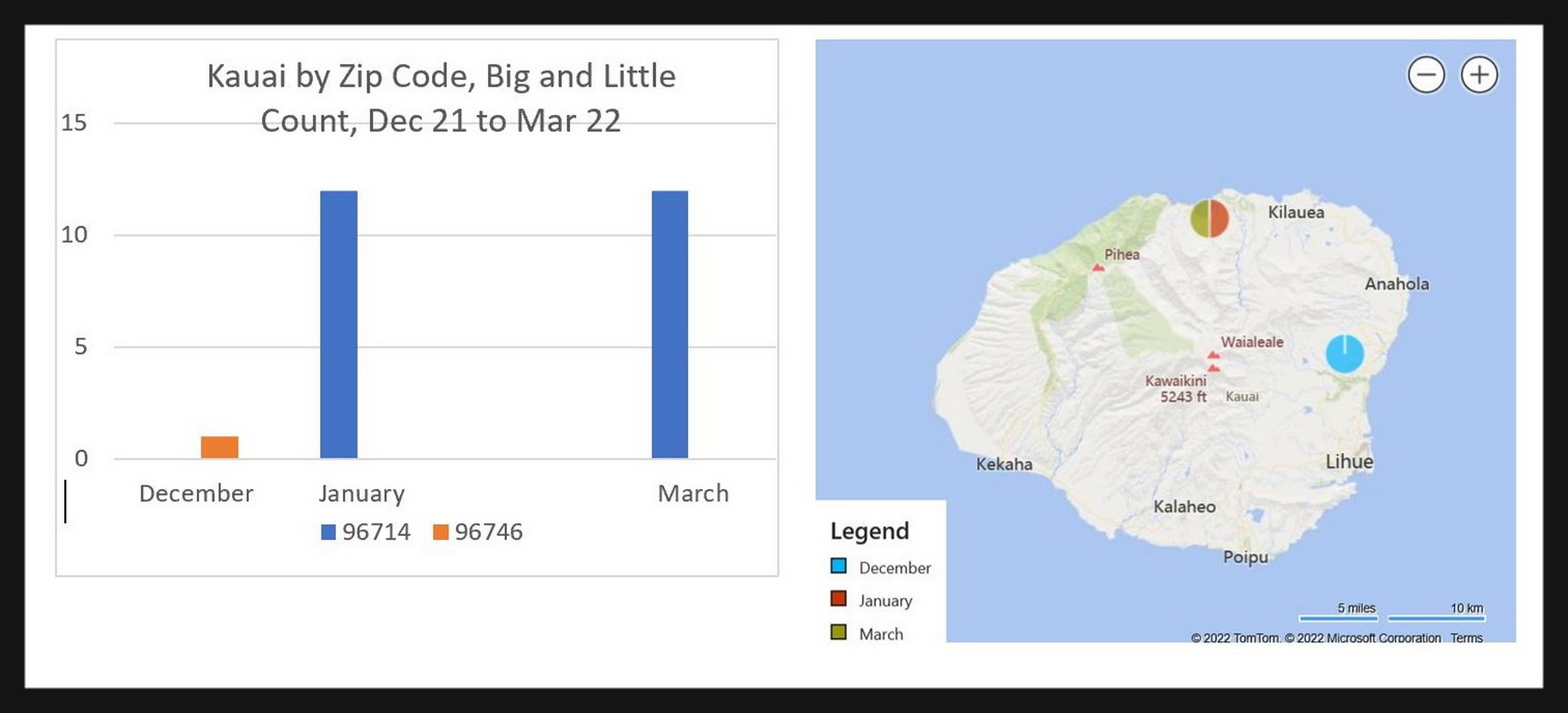

Thank you for joining the Hawaii Audubon Society’s annual statewide Kōlea Count. From December 1st through March 31st, we ask Hawaii’s participants of Big Counts to count kōlea in a park, cemetery, golf course, or other area claimed by kōlea as winter feeding sites. Little Counts are a way to note the arrival, departure, and behavior of a single bird that spends the winter in your backyard, street corner, or school grounds.

Once a plover survives its first year in Hawaiʻi, the bird returns to that precise place year after year. Foraging patches range in size from about one acre to a football field, depending on the abundance of crawly things in the patch. Kolea eat anything they can catch and swallow, including slugs (above), cockroaches, centipedes, and spiders. ©Pat Moriyasu

Once a plover survives its first year in Hawaiʻi, the bird returns to that precise place year after year. Foraging patches range in size from about one acre to a football field, depending on the abundance of crawly things in the patch. Kolea eat anything they can catch and swallow, including slugs (above), cockroaches, centipedes, and spiders. ©Pat Moriyasu

Choose a site from this list and email your choice to me, Susan Scott, here. If your area isn’t listed, tell me and I’ll add it. Please count, and report separately, your place at least three times throughout the season to account for birds that might have been startled into flight.

When a disturbance passes, a plover returns to its chosen patch, such as this bird at popular Ko Olina Lagoon 3, January 2023. ©Susan Scott

When a disturbance passes, a plover returns to its chosen patch, such as this bird at popular Ko Olina Lagoon 3, January 2023. ©Susan Scott

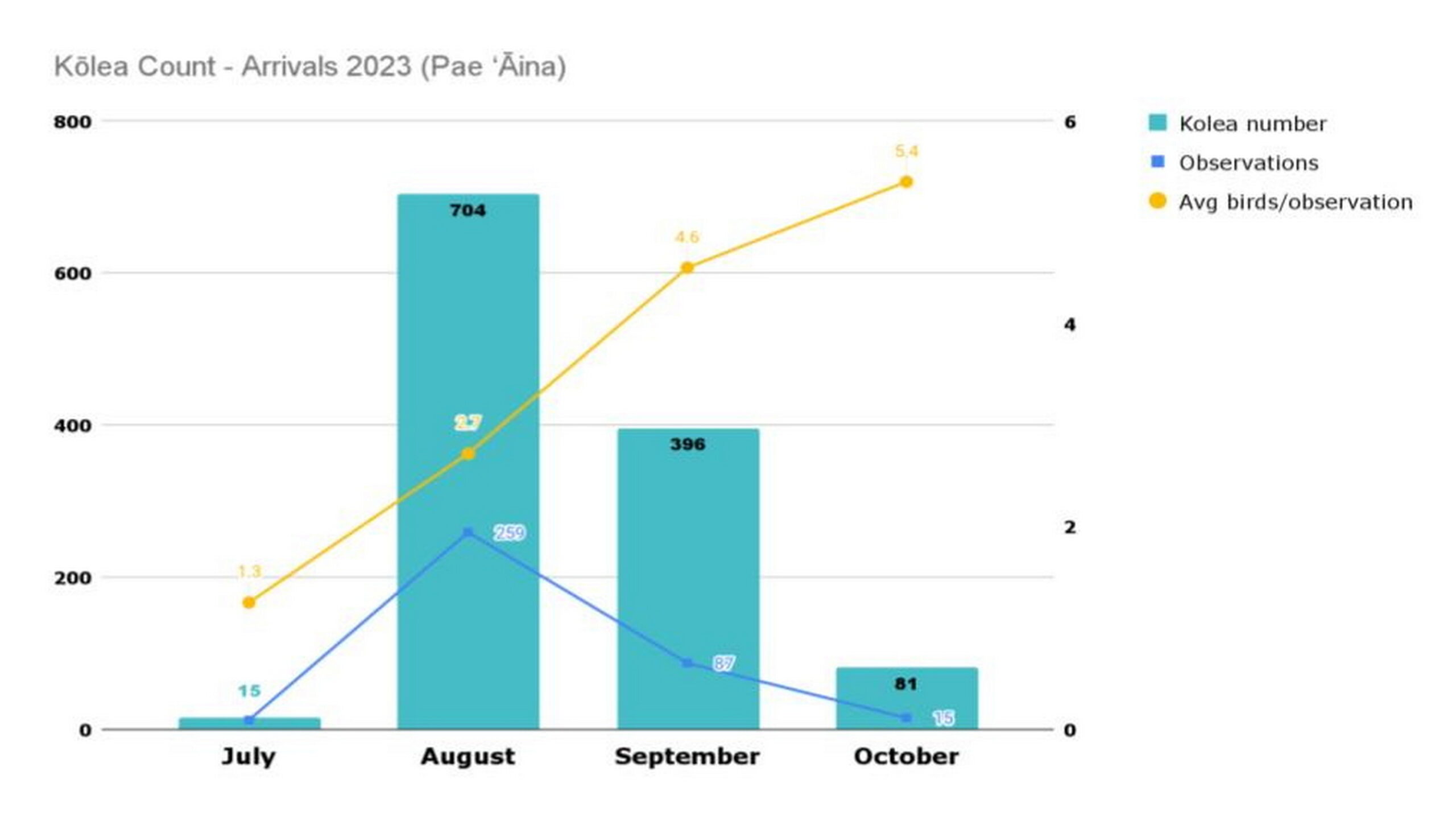

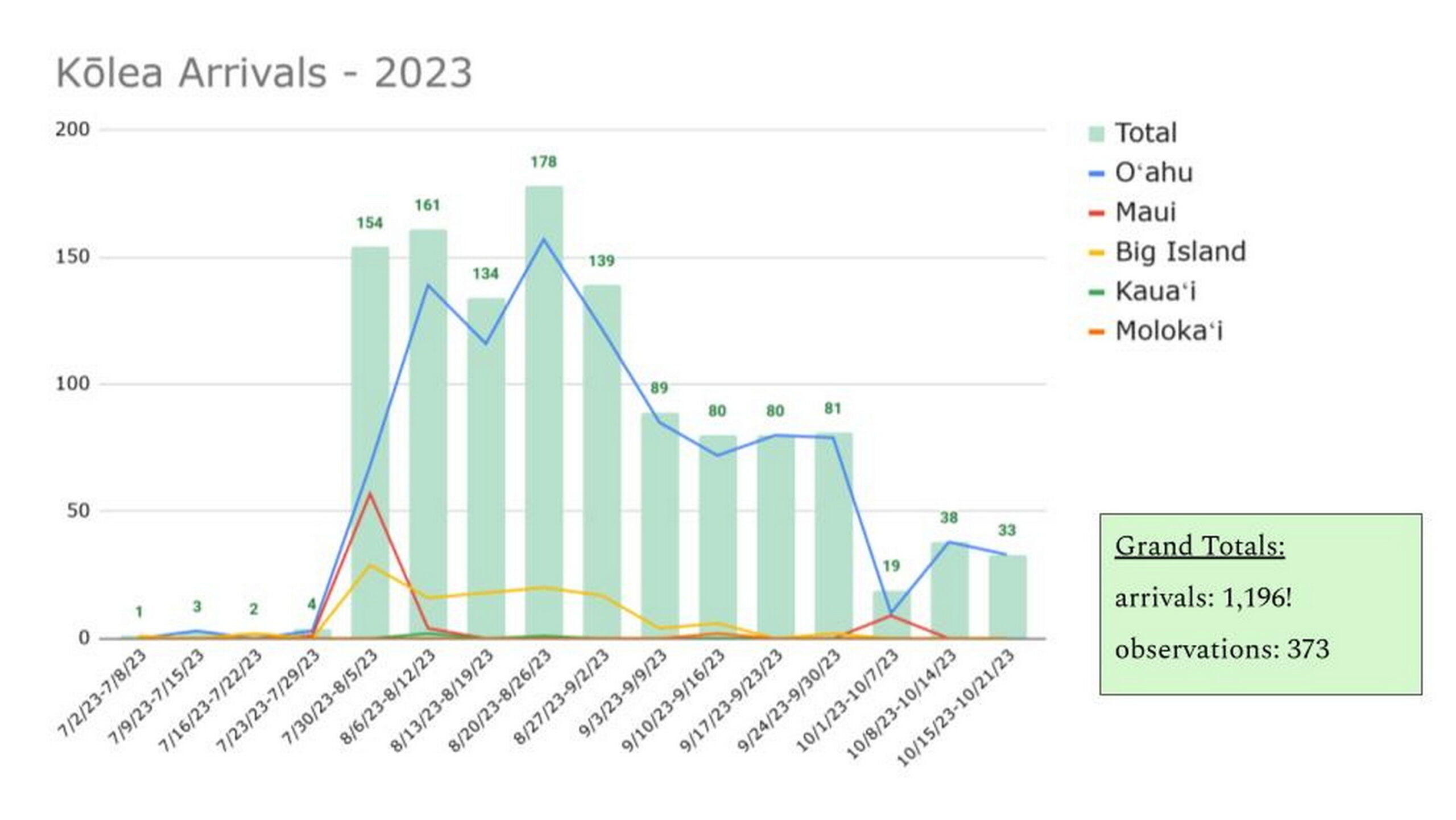

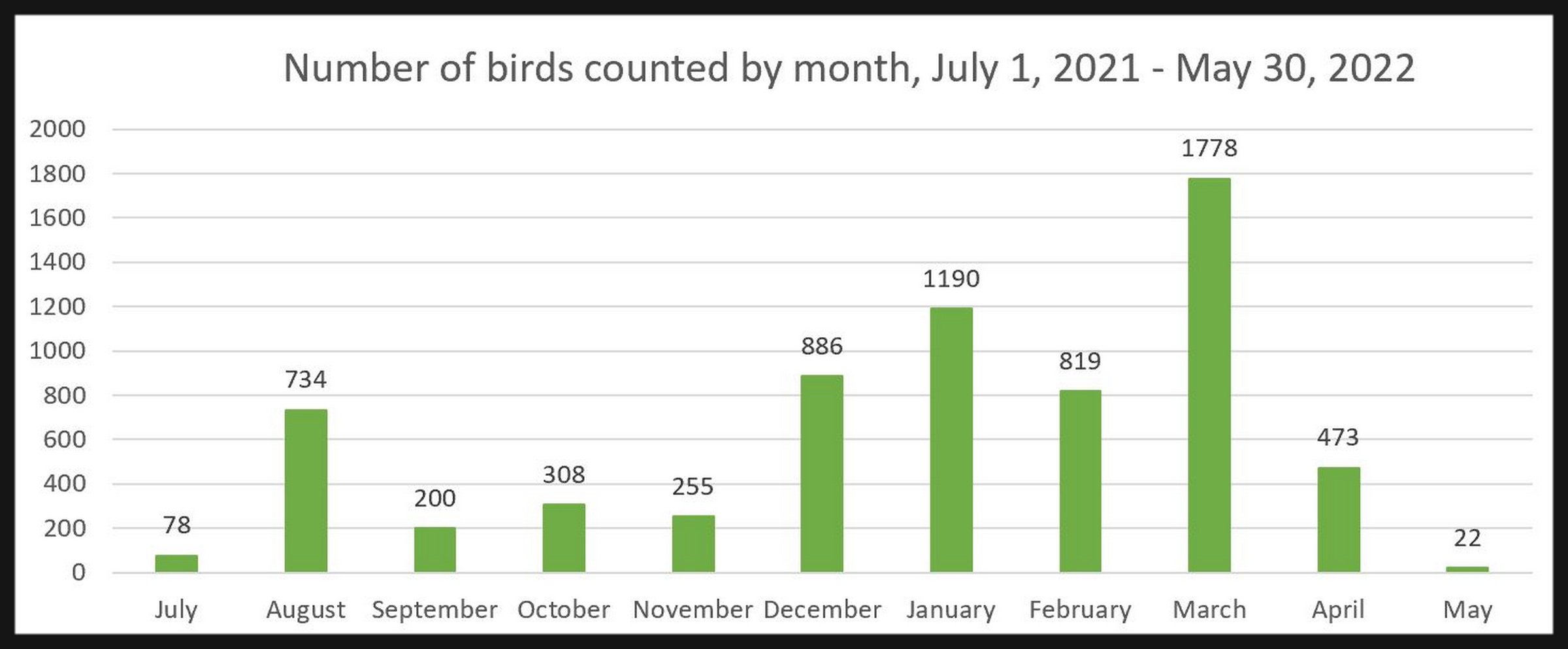

In recording our observations, we kōlea fans gather facts that help researchers learn more about the birds, and in that, help them thrive and survive. For instance, when people have noticed kōlea in late July and early August, a common question is: “Isn’t this early for the birds’ return?”

No. This summer and fall, observers reported more birds arriving in August than September. When I shared this fact to longtime plover fan and counter, Sigrid Southworth, she said, “And all these years, we said they arrived in September.”

A big mahalo to plover lovers for taking the time to report arrival dates, and to shorebird researcher Claire Atkins of UHM for compiling results in the below graphs. Also, thanks for sending pictures. If you have photos to share, please email me and I’ll send a link.

Jake arrived August 11th this year. Here he is this morning eating scrambled egg, rich in fat and protein, and just what he needs. ©Susan Scott

Jake arrived August 11th this year. Here he is this morning eating scrambled egg, rich in fat and protein, and just what he needs. ©Susan Scott  Our Jake, April 25th, plump and dressed to the nines. ©Susan Scott

Our Jake, April 25th, plump and dressed to the nines. ©Susan Scott  Photographer and kōlea fan, Robert Weber, shared this photo he took of a kōlea flock near Kahuku on October 13. These birds may be summer offspring that made it from Alaska to Hawaiʻi. Plover youngsters, have no adult guidance. Navigation is by instinct.

Photographer and kōlea fan, Robert Weber, shared this photo he took of a kōlea flock near Kahuku on October 13. These birds may be summer offspring that made it from Alaska to Hawaiʻi. Plover youngsters, have no adult guidance. Navigation is by instinct.

Chicks hatch in the order the female laid the eggs. The top center chick, still wet, was the last to hatch. The parents immediately pick up the empty eggshells and drop them far from the nest, since the white shell interiors are a visible clue to predators. The flesh-colored bumps are the chicks’ long, adult-size legs folded beneath them. ©Susan Scott

Chicks hatch in the order the female laid the eggs. The top center chick, still wet, was the last to hatch. The parents immediately pick up the empty eggshells and drop them far from the nest, since the white shell interiors are a visible clue to predators. The flesh-colored bumps are the chicks’ long, adult-size legs folded beneath them. ©Susan Scott  This photo from one of Wally’s past trips shows a male parent protecting his newly hatched offspring. © O.W. Johnson

This photo from one of Wally’s past trips shows a male parent protecting his newly hatched offspring. © O.W. Johnson  Late snowfall leaves little for newly arrived kōlea to eat. © Jim Dory

Late snowfall leaves little for newly arrived kōlea to eat. © Jim Dory  After their 3,000-mile nonstop flight, kōlea need nourishment fast. When mosquitoes and other insects hatch late due to cold weather, kōlea eat freeze-dried berries from the previous fall. © Jim Dory.

After their 3,000-mile nonstop flight, kōlea need nourishment fast. When mosquitoes and other insects hatch late due to cold weather, kōlea eat freeze-dried berries from the previous fall. © Jim Dory.  To find a nest in the vast tundra, Alaska researchers, Nancy and Paul Brusseau, watch where a flying kōlea landed. Craig Thomas (my husband) in shorts, works hard here supervising. ©Susan Scott

To find a nest in the vast tundra, Alaska researchers, Nancy and Paul Brusseau, watch where a flying kōlea landed. Craig Thomas (my husband) in shorts, works hard here supervising. ©Susan Scott

Our male, Jake, (left) usually defends his foraging territory from other birds but come April, he tolerates company, such as this attractive female. ©Susan Scott

Our male, Jake, (left) usually defends his foraging territory from other birds but come April, he tolerates company, such as this attractive female. ©Susan Scott  Plover fan, Roger Kobayashi, escorted me onto Ford Island (military ID required) to see the gathering near the NOAA building. ©Susan Scott

Plover fan, Roger Kobayashi, escorted me onto Ford Island (military ID required) to see the gathering near the NOAA building. ©Susan Scott  Hawaiʻi Audubon board member and kōlea fan, Pat Moriyasu, shot this funny photo of a kōleaʻs “skirt” during one of our blustery days in early March.

Hawaiʻi Audubon board member and kōlea fan, Pat Moriyasu, shot this funny photo of a kōleaʻs “skirt” during one of our blustery days in early March.

This bird carried, round trip, a GPS tag labeled DUMMY. It was the same weight and size as the live tags, but did not transmit a signal. ©Susan Scott

This bird carried, round trip, a GPS tag labeled DUMMY. It was the same weight and size as the live tags, but did not transmit a signal. ©Susan Scott  This male, nicknamed Mr. Necker, flew to Alaska, then Russia, then to Necker Island in the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument where his signal stopped. The team was surprised and delighted to recapture him in Punchbowl Cemetery on October 10th in the exact spot he was tagged in March. We know the bird’s sex from his springtime feather colors, not his above October colors. ©Susan Scott

This male, nicknamed Mr. Necker, flew to Alaska, then Russia, then to Necker Island in the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument where his signal stopped. The team was surprised and delighted to recapture him in Punchbowl Cemetery on October 10th in the exact spot he was tagged in March. We know the bird’s sex from his springtime feather colors, not his above October colors. ©Susan Scott  A large part, and purpose, of Kōlea research is teaching. Here’s Wally shows volunteers and students a recaptured plover’s flight feathers. ©Susan Scott

A large part, and purpose, of Kōlea research is teaching. Here’s Wally shows volunteers and students a recaptured plover’s flight feathers. ©Susan Scott  Wally shows volunteers and students the wear on a kōlea’s flight feathers. The bird will drop these hard-used feathers and grow new ones, but gradually, so as to not lose its ability to fly. ©Susan Scott

Wally shows volunteers and students the wear on a kōlea’s flight feathers. The bird will drop these hard-used feathers and grow new ones, but gradually, so as to not lose its ability to fly. ©Susan Scott

Birdy Big Foot: Kōlea chicks hatch with adult-sized feet and legs, and can fly in about a month. This chick is on the tundra near Nome, Alaska. © Oscar W. Johnson.

Birdy Big Foot: Kōlea chicks hatch with adult-sized feet and legs, and can fly in about a month. This chick is on the tundra near Nome, Alaska. © Oscar W. Johnson.  T-shirts available at hiaudubon.org.

T-shirts available at hiaudubon.org.

Kōlea pick bugs from Astroturf and bathe in hotel swimming pools. Kauai. ©Susan Scott

Kōlea pick bugs from Astroturf and bathe in hotel swimming pools. Kauai. ©Susan Scott  Punchbowl Cemetery, Oahu’s Kōlea lab. © Sigrid Southworth (our Punchbowl Kōlea counter.)

Punchbowl Cemetery, Oahu’s Kōlea lab. © Sigrid Southworth (our Punchbowl Kōlea counter.)

Wally and me (Susan) giving a Kōlea ID leg bands at Punchbowl Cemetery, March, 2022.

Wally and me (Susan) giving a Kōlea ID leg bands at Punchbowl Cemetery, March, 2022.

The above clip is from the September 3rd, 2022 Kokua Line. My answers are available only to Star-Advertiser subscribers, but the facts I gave Christine are below, as well as on this website. On September 9th, I also chatted about kōlea with Catherine Cruz, host of Hawaii Public Radio’s “The Conversation.”

The above clip is from the September 3rd, 2022 Kokua Line. My answers are available only to Star-Advertiser subscribers, but the facts I gave Christine are below, as well as on this website. On September 9th, I also chatted about kōlea with Catherine Cruz, host of Hawaii Public Radio’s “The Conversation.”  Between 70 and 80 kōlea spend winters in Punchbowl Cemetery. This is the first to arrive back in its Punchbowl patch, spotted by the Hawaii Audubon Society’s office and communications manager, Laura Zoller on August 7, 2022. ©Laura Zoller

Between 70 and 80 kōlea spend winters in Punchbowl Cemetery. This is the first to arrive back in its Punchbowl patch, spotted by the Hawaii Audubon Society’s office and communications manager, Laura Zoller on August 7, 2022. ©Laura Zoller  This bird posed perfectly for a picture of its leg bands. The plover returned to Punchbowl on August 22nd, and appeared to be good health after flying 6,000 round-trip miles carrying a tiny satellite tag. (antenna below tail.) © Susanne Spiessberger

This bird posed perfectly for a picture of its leg bands. The plover returned to Punchbowl on August 22nd, and appeared to be good health after flying 6,000 round-trip miles carrying a tiny satellite tag. (antenna below tail.) © Susanne Spiessberger

Our Jake on April 1st. ©Susan Scott

Our Jake on April 1st. ©Susan Scott  During my visit to the Ford Island field, Roger and I counted about 50 birds in the field. Because they tended to line up lengthwise, less than half are visible in this picture. ©Susan Scott

During my visit to the Ford Island field, Roger and I counted about 50 birds in the field. Because they tended to line up lengthwise, less than half are visible in this picture. ©Susan Scott  Punchbowl study female, April 20, 2022.©Susan Scott

Punchbowl study female, April 20, 2022.©Susan Scott  Another Punchbowl study male, April 26, 2022 ©Susan Scott

Another Punchbowl study male, April 26, 2022 ©Susan Scott