Punchbowl’s Kolea get backpacks and bracelets

Dr. Wally Johnson with feathered friend, National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. ©Susan Scott

Dr. Wally Johnson with feathered friend, National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. ©Susan Scott

March 30, 2022

Our Kolea’s long-term advocate and life-long researcher, Dr. Wally Johnson of Montana State University, has been on Oahu these last few weeks helping the world learn more about one of Hawai’i’s (and Wally’s) favorite birds. In a study supported by Brigham Young University-Hawaii, the Hawaii Audubon Society, the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, and enthusiastic volunteers, Wally is placing leg bands on nearly half of the 60-to-70 Kolea that forage in the cemetery each winter.

Above: These ID bands are visible on foraging birds (binoculars or enlarging photos help.) To report a banded bird, note which bands are on which leg. This bird has blue on left leg, yellow and aluminum on right. ©Susan Scott

Each of 30 birds gets three leg bands, two plastic in various colors, and a numbered aluminum one, recorded by the North American Bird Banding Program. The colors allow observers to identify an individual without disturbing it.

This is how we know that Mr. X, a Punchbowl plover, is at least 19 years old. Wally gave the bird two red plastic leg bands (one went missing last year), and one aluminum, in section X in April, 2004. He says “at least 19” because the bird’s age was unknown when banded and, therefore, may be older.

Of the 30 plovers in Wally’s current study, 10 are fitted with tiny backpack tags that send GPS signals via satellite twice a day for about six months. Another 10 will carry identical tags sending no signal. The last 10 have only leg bands. This fall, Wally will be back to monitor the birds’ survival.

The plover carries its lightweight satellite tag on its back with soft, stretchable straps around the upper part of each leg. This allows the birds to walk and fly unhindered. ©Susan Scott

The plover carries its lightweight satellite tag on its back with soft, stretchable straps around the upper part of each leg. This allows the birds to walk and fly unhindered. ©Susan Scott

The 10 with signals will hopefully show the birds’ movements here in Hawaii, their tracks to Alaska, their nesting sites, and tracks back to Hawaii. The 10 with no signals will test the possibility that electronic tags interfere with natural navigation cues. Survival of the 10 with bands only will test whether simply carrying a backpack tag negatively affects the bird’s natural navigation system.

Volunteer, Marcy Katz, enjoys holding a satellite-tagged bird (antenna below its tail) before releasing it. Because Pacific Golden-Plovers defend their foraging areas, Wally makes sure each bird is returned to its home patch to avoid squabbles. ©Susan Scott

Volunteer, Marcy Katz, enjoys holding a satellite-tagged bird (antenna below its tail) before releasing it. Because Pacific Golden-Plovers defend their foraging areas, Wally makes sure each bird is returned to its home patch to avoid squabbles. ©Susan Scott

I’m smiling as I write the above paragraphs, because it sounds simple. It is not. Studies like this require years of experience. Nor do scientists just go to a store and buy satellite tags. At $1,600 each, these devices must be specially ordered and used in a timely manner, given limited shelf life of the batteries. Lastly, you have to catch birds that are …

This Maui Kolea enjoyed bathing in a driveway rain puddle. © Photo courtesy Calvin M. Kaya, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Biology, Montana State University

This Maui Kolea enjoyed bathing in a driveway rain puddle. © Photo courtesy Calvin M. Kaya, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Biology, Montana State University  Craig is showing off the Pacific Golden-Plover patch on my Alaska Audubon hat, a special gift. Friend and neighbor Lani Twomey braved the storm to count Kolea with us. (Selfie)

Craig is showing off the Pacific Golden-Plover patch on my Alaska Audubon hat, a special gift. Friend and neighbor Lani Twomey braved the storm to count Kolea with us. (Selfie)  The Christmas Day Kolea team from right, David Johnson. Beth Flint, Craig Thomas and me, Susan Scott. Photo by Michelle Hester

The Christmas Day Kolea team from right, David Johnson. Beth Flint, Craig Thomas and me, Susan Scott. Photo by Michelle Hester  During the storm, stilts, ducks and people enjoyed the temporary lake on this fairway. © Susan Scott

During the storm, stilts, ducks and people enjoyed the temporary lake on this fairway. © Susan Scott  For reasons known only to the Kolea, the birds sometimes line up on the runway at Midway Atoll. © Courtesy Jonathan Plissner, USFWS

For reasons known only to the Kolea, the birds sometimes line up on the runway at Midway Atoll. © Courtesy Jonathan Plissner, USFWS

This Jaeger (pronounced YAY-gur, German for hunt) is a fast-flying gull relative that, like Kolea, nests on the ground in the Arctic tundra. Jaegers are predators that eat other birds and their eggs. This post on the tundra outside Nome was a good perch for scouting prey. ©Susan Scott

This Jaeger (pronounced YAY-gur, German for hunt) is a fast-flying gull relative that, like Kolea, nests on the ground in the Arctic tundra. Jaegers are predators that eat other birds and their eggs. This post on the tundra outside Nome was a good perch for scouting prey. ©Susan Scott  Although usually spread out on the sides of the Dillingham Airfield, these Kolea gathered on on the roadside during sky-diving activities. ©Susan Scott

Although usually spread out on the sides of the Dillingham Airfield, these Kolea gathered on on the roadside during sky-diving activities. ©Susan Scott

Ms. Ed. ©Susan Scott

Ms. Ed. ©Susan Scott  Bilbo taking a shower. ©Susan Scott

Bilbo taking a shower. ©Susan Scott  Roger Kobayashi sent a Google map of Ford Island, marking X, Y, and Z as to his first Kolea sightings, August 1, 2021.

Roger Kobayashi sent a Google map of Ford Island, marking X, Y, and Z as to his first Kolea sightings, August 1, 2021.  Wally, the bird, enjoying a scrambled egg offering. Please feed your bird only healthy food, such as scrambled egg or mealworms. ©Roger Kobayashi

Wally, the bird, enjoying a scrambled egg offering. Please feed your bird only healthy food, such as scrambled egg or mealworms. ©Roger Kobayashi

Mr. X in his territory in March, 2021 with all three leg bands. ©Sigrid Southworth.

Mr. X in his territory in March, 2021 with all three leg bands. ©Sigrid Southworth.  Researchers can place adult-sized leg bands, shown here, on newly hatched Kolea chicks. The youngsters begin foraging for insects and berries soon after hatching. Parents warm and protect their offspring, but do not feed them. Near Nome, Alaska © Oscar Johnson. …

Researchers can place adult-sized leg bands, shown here, on newly hatched Kolea chicks. The youngsters begin foraging for insects and berries soon after hatching. Parents warm and protect their offspring, but do not feed them. Near Nome, Alaska © Oscar Johnson. …

Signs on Anchorage’s Tony Knowles Coastal Trail explain how to behave when confronted by a moose. I thought such an encounter unlikely. I was wrong. ©Susan Scott

Signs on Anchorage’s Tony Knowles Coastal Trail explain how to behave when confronted by a moose. I thought such an encounter unlikely. I was wrong. ©Susan Scott  A moose on the trail brought me, on my rented bike, to a screeching halt. ©Susan Scott

A moose on the trail brought me, on my rented bike, to a screeching halt. ©Susan Scott  I waited until the moose lost interest in me and ambled off into the woods that border urban Anchorage. ©Susan Scott

I waited until the moose lost interest in me and ambled off into the woods that border urban Anchorage. ©Susan Scott  A clear picture of a semipalmated plover. D. Gordon E. Robertson photo, Creative Commons, Wikipedia.

A clear picture of a semipalmated plover. D. Gordon E. Robertson photo, Creative Commons, Wikipedia.  My first sighting of a semipalmated plover. This is just feet off the Homer Spit road (sign top left.) ©Susan Scott

My first sighting of a semipalmated plover. This is just feet off the Homer Spit road (sign top left.) ©Susan Scott

Resting up for the big trip. BYUH campus. ©Susan Scott

Resting up for the big trip. BYUH campus. ©Susan Scott

Sig’s discovery is excioting news. The last time Wally Johnson banded Kolea in Punchbowl was over 18 years ago, making this individual a minimum of 18 years, 6 months old. The bird might be older. Wally didn’t know the bird’s age when he placed the bands on its leg. Sigrid Southworth photo

Sig’s discovery is excioting news. The last time Wally Johnson banded Kolea in Punchbowl was over 18 years ago, making this individual a minimum of 18 years, 6 months old. The bird might be older. Wally didn’t know the bird’s age when he placed the bands on its leg. Sigrid Southworth photo  Heads-up: If you go to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl), an excellent place to watch plovers, rules of respect are enforced. I have been warned twice by security guards that neither walking (meaning strolling about) nor bird watching not allowed. Visiting graves or memorials, however, is fine. Now when I’m there, and they ask, I am “visiting.” Susan Scott photo.

Heads-up: If you go to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl), an excellent place to watch plovers, rules of respect are enforced. I have been warned twice by security guards that neither walking (meaning strolling about) nor bird watching not allowed. Visiting graves or memorials, however, is fine. Now when I’m there, and they ask, I am “visiting.” Susan Scott photo.  My update on the Kolea Count is Thursday, April 1st at 6:30 via live Zoom. Register to join me.

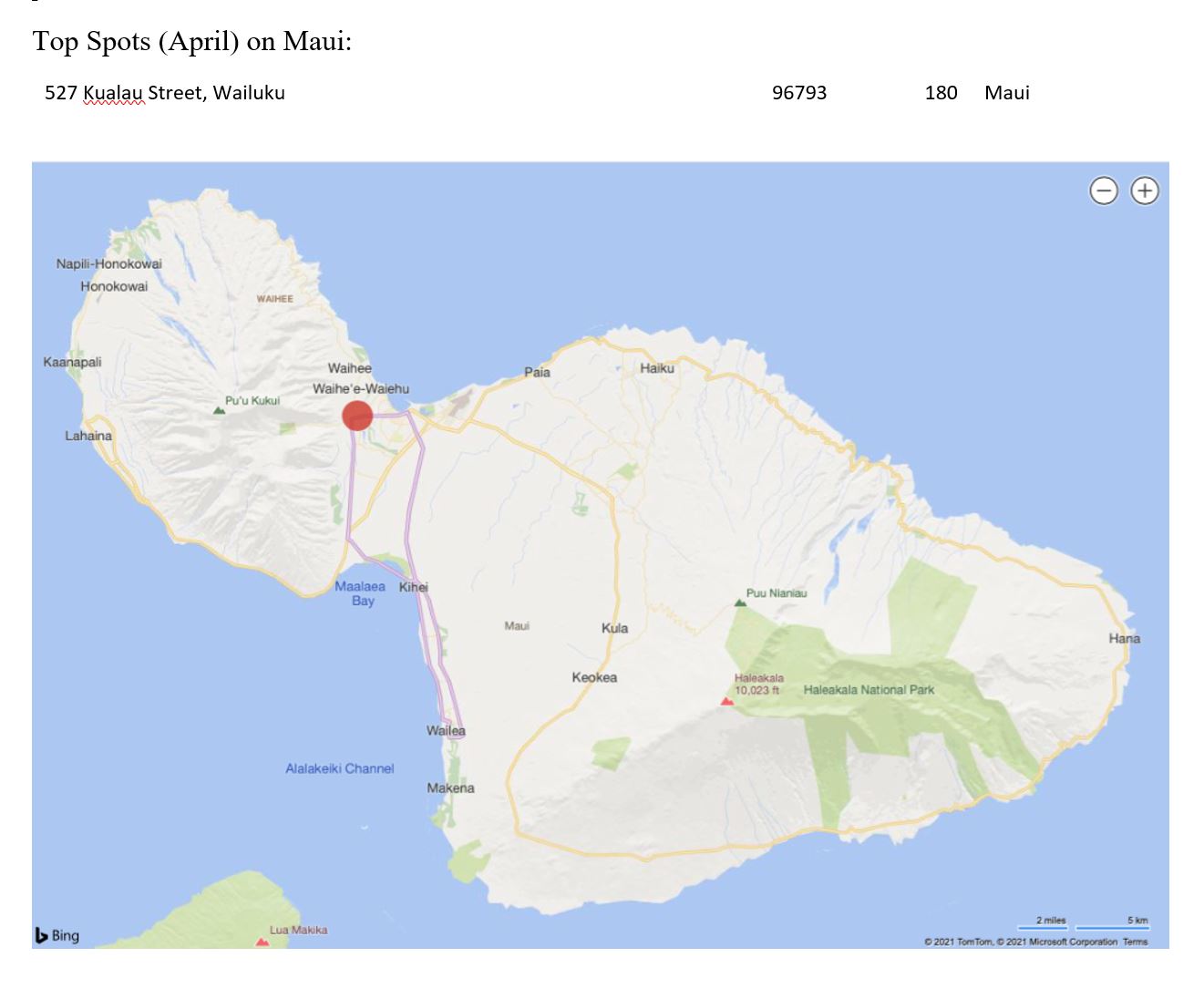

My update on the Kolea Count is Thursday, April 1st at 6:30 via live Zoom. Register to join me.